Published in The New York Times, November 26, 2006

The (Naked) City and the Undead

By Tom WolfeCHIN up, tummy out, Aby Rosen, the 46-year-old German developer, owner of the Seagram Building and Lever House, was posing for pictures in front of 980 Madison Avenue barely one month ago when he grew so bold as to boast: “I have zero fear. Fear is not something I have.”

Easy for you to say, braveheart! The courage-crowing tycoon knows very well that in the current battle over 980 Madison, a five-story Art Moderne building stretching from 76th Street to 77th Street, the contest is already completely snookered in his favor.

On top of this block-long low-rise he intends to build one of his Aby Rosen jumbo glass boxes full of commercial space and condominiums, rising straight up a sheer 30 stories. His big problem — or, to be more accurate, “problem” — is that 980 Madison is in the heart of the Upper East Side Historic District, and it would be hard to dream up anything short of a Mobil station more out of place there than a Mondo Condo glass box by Aby Rosen.

The writer Tom Wolfe and other neighbors have taken to lobbing objections in the direction of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the city’s official watchdog for landmarked areas. The commission has already held a hearing and could stop Aby Rosen dead in his tracks at a moment’s notice, just like that.

But what, him worry? Like every major developer in town, he knows that the Landmarks Preservation Commission has been de facto defunct for going on 20 years. Today it is a bureau of the walking dead, tended by one Robert B. Tierney.

Mr. Tierney and the 10 members of his commission already have a hearty, comrades-in-arms, marching-along-together history with Aby Rosen. The commission was highly instrumental last November in clearing the way for him to build a zone-busting glass box full of condominiums on Lexington Avenue and 53rd Street in return for his guarantee, written into the deed, that the exterior of his Seagram Building, given landmark status in 1989, will be maintained in its original condition in perpetuity.

Mr. Tierney gushed — insofar as one can gush in a press release — that Aby Rosen was not only ensuring “the highest level of protection” for this historic building, he was also being so kind as to favor New York with “a landmark of the future,” namely, his glass box godzilla at Lexington and 53rd.

How generous! How civic-minded! Noblesse oblige! ... until one reminds oneself that Aby Rosen and every other owner of a landmarked building is required by law to maintain it in its original condition.

Aby Rosen is a global success story of the 21st century, a citizen of the world. He should care about New York’s parochial steps to make historic preservation a government responsibility?

That was in another century, the 20th, 1965 to be exact, after a developer had demolished that old solemn-columned classical temple of passenger train travel, Pennsylvania Station, to make way for Madison Square Garden, a coliseum where the rabble could go watch hungover Canadians on ice skates batter one another senseless.

Never again! vowed le tout New York. The thrill of a Goo-Goo crusade thrummed through the gizzard of everyone from, eventually, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and legions of other celebrities and socialites to virtually every prominent politician, from Mayor Robert F. Wagner on down.

Never again! The City Council gave legal muscle to a previously powerless Landmarks Preservation Commission, made up of scholars, city planners, architects, artists, landscapers, designers. This was to be an aesthetic and scholarly elite with virtually absolute discretion in deciding what buildings and historic districts should be preserved forever through landmark designation.

Goo-Goo was an old City Hall term for believers in Good Government, by which the regulars meant idealistic lightweights whose feet seldom touched the ground. But all at once every big shot in New York seemed to have gone Goo-Goo.

So feverish was that born-again bliss that for a decade the commission pretty much had its idealistic way. But when the commission tapped for protection the city’s other great monument to railroad travel, Grand Central Terminal, it wound up in a do-or-die lawsuit that reached the United States Supreme Court in 1978.

Goo-Goo fever now shot up to a peak. Jackie O. herself served as the star passenger on the Landmarks Express, a private train packed with celebrities, socialites and members of the commission who headed to Washington to exhort the court to uphold New York’s landmarks law — and in so doing save the station. Mayor Edward I. Koch gave a Goo-Goo, Never Again send-off speech so moving that cynical, battle-hardened, social-cliff-climbing Manhattan matrons had to dab their eye sockets. Not even the Supreme Court justices, it seemed, could control themselves in a Camelot moment. They upheld the landmarks law faster than you could say Oh, Jackie, ohhhhh ...

Oooooooooohhhhhhhhhhhh yes, went the landmarks commissioners. The chairman received a salary, but the commissioners got no pay for this job. Still, the psychic rewards were turning out to be awesome. You were working for a cause you believed in, and at a high and highly visible level. After all, you were now an official of the 20th century’s capital of the world, New York City, and you kept running into the very rich and very social — who were suddenly giving you aero-kisses, Euro-style, four millimeters away from each side of your face.

The commissioners had made names for themselves professionally as scholars, architects, city planning consultants, but now they were moving up in life in a way they could have never anticipated. One evening a commissioner from the Jackie O. period is at a cocktail party — you were now being invited to an infinitely better class of parties — when a benefactress of the City Beautiful movement approaches him and asks if he would like to go over to Lincoln Center and watch Jerome Robbins rehearsing with Mikhail Baryshnikov for some ballet that’s coming up. The next thing he knows, her driver is taking the two of them over to the theater.

“The place is dark except for the stage,” he recounted, “and there’s Jerome Robbins up there, and Baryshnikov, and Robbins is having Baryshnikov try this and try that — and the only people in the whole audience are this woman and me! Us and some Saudi prince who’s backing the show.”

You would walk into a conference room and people would jump up and shake your hand and take your coat and show you to a seat and smile and beam, beam, beam respect — because you and your commission colleagues wielded a government power over private property second only to confiscating it via the right of eminent domain. When you made someone’s property a landmark, he retained title to it, but you confiscated his ability to exploit it by putting up something new in its place or selling it for development. In a former commissioner’s own words: “One day it dawns on you. You’re pushing around billions of dollars worth of real estate development. You’re telling the biggest developers in the world, ‘Keep moving, Jack! You can’t build there!’ ”

Somehow you had made it inside the Walled City that Theodore Dreiser described in “Sister Carrie.” There was New York the melting pot, the boiling stew, of the eight million ... and there was the Walled City, wherein existed New York’s fabled excitement and glamour and power and blinding wealth and extravagant ease and fine slim people who introduced you to restaurants where you didn’t dare order a beer and wished you hadn’t worn a brown suit and a “colorful” necktie. Thus it came to be that turnover on the commission was exceedingly low.

No fools, New York’s mayors got the picture soon enough. Why on earth allow so much power to remain in the hands of a bunch of arty, sentimental, cerebral, status-addicted Goo-Goos? And the name of the man who first made City Hall’s contempt obvious? Edward I. Koch! The very man who had left them sobbing Goo-Goo tears during the Camelot moment! Not the velvet-gloved sort, Mr. Koch went ballistic in what became the notorious Tung affair.

In 1987, for good and sufficient civic and political reasons, the mayor wanted to turn Bryant Park, the badly rundown open space behind the New York Public Library, into a gloriously landscaped Tuileries Garden for Manhattan crowned with a Lucullan restaurant. But building the restaurant would mean cutting down a stand of towering old trees. The mayor wanted the commission to give this alteration its blessing.

Enter Anthony M. Tung. Mr. Tung was only 37 but had served on the commission for eight years. One and all agreed he was probably the most erudite member the commission had ever had, a city planning consultant, a walking encyclopedia of the history, principles and practices of urban preservation, and a brilliant analyst; in short, a genius in that field.

Mr. Tung argued that the proposed restaurant would be a landmark desecration, butchering not only many magnificent old trees but also the entire rear aspect of the library, which was every bit as innovative and historically important as the more famous Fifth Avenue front with its lions and great staircase. So eloquent was he, so utterly convincing, that the commission, chairman and all, swung around and denied Mayor Koch’s request — unanimously — and made him look like a hairy Visigoth getting ready to sack Rome.

Impudent wretch! The mayor got word to the genius that he was fired so fast — five days later — it made the tail on the Q of Mr. Tung’s sky-high I.Q. curl.

Getting rid of him was easy, or should have been. Landmarks commissioners were appointed for three-year terms, and it turned out that Mr. Tung and six of the other nine unpaid commissioners had never been officially reappointed. They had just kept on serving. Technically, they were expirees. This was probably the result of nothing more than bureaucratic inertia. But it was very handy! All the mayor had to do was have somebody send Mr. Tung a letter saying his term had expired, he wasn’t being reappointed, so long, thanks a million for your service, and kindly go off and be a genius by yourself. In fact, thanks to the rank odor, it took the mayor months to find a both willing and respectable candidate to take his place.

Mr. Tung didn’t take it lying down for a moment, and the Tung affair boiled and stewed in the press for months. Still, no one seemed to realize at the time that the landmarks law, as originally conceived, was now null and void. From the Tung affair on, the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s aesthetic elite was pretty much free to bestow landmark status on any property it saw fit — unless the mayor had designs on it himself.

Barely a peep in Anthony Tung’s behalf was heard from any commissioner or the chairman, even though all of them had so bravely agreed with him at the outset. Well ... let’s face it. One has to render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, doesn’t one? But we’ll get to decide on the rest, won’t we? And still be invited to all the parties?

Talk about never again! Never again could you expect a landmarks commissioner, much less a chairman, to stand up to a mayor. And, as a corollary, never again could you expect any of them to stand up to Big Real Estate, if Big Real Estate had the mayor’s backing. As they say at City Hall, they got along by going along. It wasn’t so bad ... talking the talk with one’s fellow walking dead and walking the walking-dead walk to swell parties and events.

As for Anthony Tung: he went off and, a genius by himself, wrote a book titled “Preserving the World’s Great Cities.” Today it is the bible of urban preservationists all over the globe, and from Mexico City to Athens to Istanbul to Kyoto and Singapore, he is one of the world’s most sought-after speakers and consultants on urban planning, most recently in New Orleans.

The undead commission became only undeader under Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani. When he became mayor in 1994, New York had hit the bottom of a full-blown commercial real estate depression, and he wasn’t about to allow anyone with a weakness for silvery-tongues to become chairman. So he appointed a former campaign strategist, Jennifer J. Raab, who was introduced to the public as a highly experienced land-use lawyer.

Translated, that meant she made her living representing landlords and developers for the big-time, high-billing-and-the-clock-is-running law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. It didn’t take long for her to enunciate the Raab Doctrine. No longer is it Us against Them, she said. From now on everyone, preservationists and developers alike, will recognize their common interest in preservation.

With that, she bade Us lamb chops to lie down with Them lions and bestowed “preservation achievement awards” for preservation-friendly architectural designs upon the Gap — which she teasingly referred to as the “big bad corporation” by way of showing Them lions were really pussycats — and Bernard Mendik, chairman of the Real Estate Board, the lobby for landlords, developers and brokers, by natural selection the evolutionary enemies of landmarks preservation. As for the commission, it remained packed with expirees who would gladly disintegrate, if necessary, to avoid casting so much as a shadow on any of the mayor’s plans.

Reading the tank-style tread marks of the excavation earth-movers today, one is forced to conclude that Rudy Giuliani and Ed Koch are not the only mayors who would just as soon have ended the charade by mercifully putting the Landmarks Preservation Commission and the walking dead out of their misery or at least slipping them into the sleep mode the way you can a computer. Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg certainly seems to qualify as another.

Last year, as he had ever since 2003, Mayor Bloomberg made it clear that he wanted a 40-year-old white marble building the city owned at 2 Columbus Circle, designed by Edward Durell Stone for Huntington Hartford’s short-lived Gallery of Modern Art, replaced by a glass box proposed by the Museum of Arts and Design, to fit in with the behemoth glass box of the nearby Time Warner Center.

Back in the 1960s, critics and the art world in general had sniggered, sneered and hooted Mr. Hartford’s gallery into oblivion after only five years. But that was 40 years ago, and art history is chronically revisionist. (Rembrandt once got cold-shouldered for two centuries.)

Now, in 2005, the mayor was confronted by an incredible uprising of scholars, world-renowned architects, deans of art and architecture at the great universities, mega-wattage art worldlings — the greatest massing of cultural luminaries in a single cause since the anti-fascist crusades of the 1930s! — all calling upon the commission to hold a hearing, lest this historic work by a great American architect be destroyed without a second thought.

For any owner of a magnifying glass seeking a closer look at this astral army:

The two most eminent architectural historians in the United States, Vincent Scully and Robert A. M. Stern, dean of Yale’s school of architecture, a famous and prolific architect in his own right, and the definitive historian of New York architecture from the late 19th century to the present, co-author of the magisterial quintet, “New York 1880,” “ New York 1900,” “New York 1930,” “New York 1960,” “New York 2000”; nine deans and graduate program directors of art and architecture, including three from Columbia University, and one of the nation’s best-known urban studies scholars and theorists, Witold Rybczynski of the University of Pennsylvania; the most elite lineup of architects who ever stood shank to flank in a preservation controversy: Richard Meier, Cesar Pelli, Robert Venturi, Laurie Olin, Hugh Hardy and Peter Eisenman, plus Dean Stern, to single out but seven from among a host of them; the current chief architectural critic of The New York Times and two of his predecessors, one of whom called the commission’s year-after-year refusal to call a hearing “a shocking dereliction of public duty”; The Times itself, in an editorial characterizing Stone’s building as “already an architectural monument, the work of a major architect, whether the commission likes it or not” and the refusal as “an enormous mistake, one that seriously erodes [the commission’s] purpose and whatever independence it has managed to attain since it was first created”; the nation’s, New York State’s and New York City’s most highly respected preservation societies, including the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the World Monuments Fund; Agnes Gund, who had just stepped down as president of the board of the Museum of Modern Art; the artists Frank Stella and Chuck Close, under whose letterhead a petition signed by more than 50 artists went to Mayor Bloomberg; and three former chairmen of the landmarks commission.

If the administration had the subpoena power to summon a jury of the most esteemed architectural and urban planning authorities in the United States to judge the case of 2 Columbus Circle — it would have summoned the very same people who are in that condensed like-a-lump-of-coal type. There are no higher authorities. So how did Robert Tierney respond to them?

He didn’t! Not once! It was as simple as that!

He stayed holed up in his bunker at 1 Centre Street, while Spokesperson said ... and said ...and said ... and said, “Under two administrations and three chairmen, the commission has declined to consider this site for landmark status, and I am aware of no new information that would make it necessary to revisit the matter”...

“Under two administrations and three chairmen, the commission has declined to consider”...

“Under two administrations and three chairmen, the commission”...

“Under two administrations and three”...

But, but, but how could he do that without seeming ... brain dead ... or without taking direct orders? Either way, the chairman’s refusal to call a hearing — a mere hearing, which would commit the commission to nothing — or to so much as discuss a hearing ... was as good as an official proclamation:

Landmarking no longer exists in New York City, not even as a principle — or not above the level of the occasional parish house in Staten Island or rusticated old stone archway in eastern Queens.By this time last year unionized elves with air hammers had reduced 2 Columbus Circle’s white marble to rubble and set about gutting the interior.

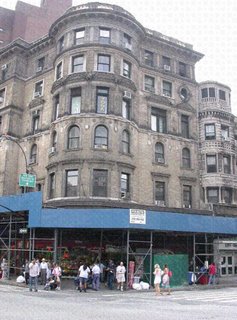

The chairman was marginally less blunt about staying out of the way of Big Real Estate. For two decades preservation groups had been petitioning the commission to give landmark status to the five-story Romanesque Revival-style Dakota Stable on Amsterdam Avenue at 77th Street, the most important remaining relic of late 19th century New York’s palmy days of riding horses and traveling by horse-drawn carriage.

This spring they learned that Big Real Estate, in the form of the Related Companies, developers of the Time Warner Center, had a contract to buy the building with the intention of demolishing it and putting up 14 stories’ worth of condominiums. (Ironically, they picked Robert Stern as the architect.) In July, Mr. Tierney indicated he was going to hold a hearing ... hold a hearing ... hold a hearing ... hold a hearing ... but was somehow delayed until Oct. 17 — and wouldn’t you know it? In September the city had granted permission to alter the Dakota Stable and by Oct. 17 it had been stripped of its architectural details, and all that was left was “a stucco box.”

Those were the chairman’s own words, “a stucco box.” Just the other day he shook his head and declared it was too late to do anything about that.

SO we will never know about Aby Rosen! Maybe the man does have “zero fear.” But he won’t be put to the test this time. In the case of 980 Madison he has one-click approval whenever They feel the time is right.

In case he’s wondering, he should know that the table is set at the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Set beautifully! Never better! Nine of the 10 current commissioners, not counting Mr. Tierney, are expirees — 90 percent! — in imminent danger of getting canned if they don’t do the right thing by Aby Rosen!

Once upon a time, in the legendary age of Camelot, back when Jackie O. could make the entire United States Supreme Court roll over and moan, it was the landlords and developers who used to scream bloody murder at the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Just two weeks ago close to 100 leaders of New York City preservationist groups held a “citizens emergency meeting” at the General Society Library on West 44th Street... and bayed for the blind goddess, Justice, to make Preservation the commission’s middle name. Many of them were young, young enough to envision a landmarking renaissance. Youth! The way they bayed was enough to make the hair stand up on old Aby Rosen’s arm.

Tom Wolfe is the author, most recently, of “I Am Charlotte Simmons.”’